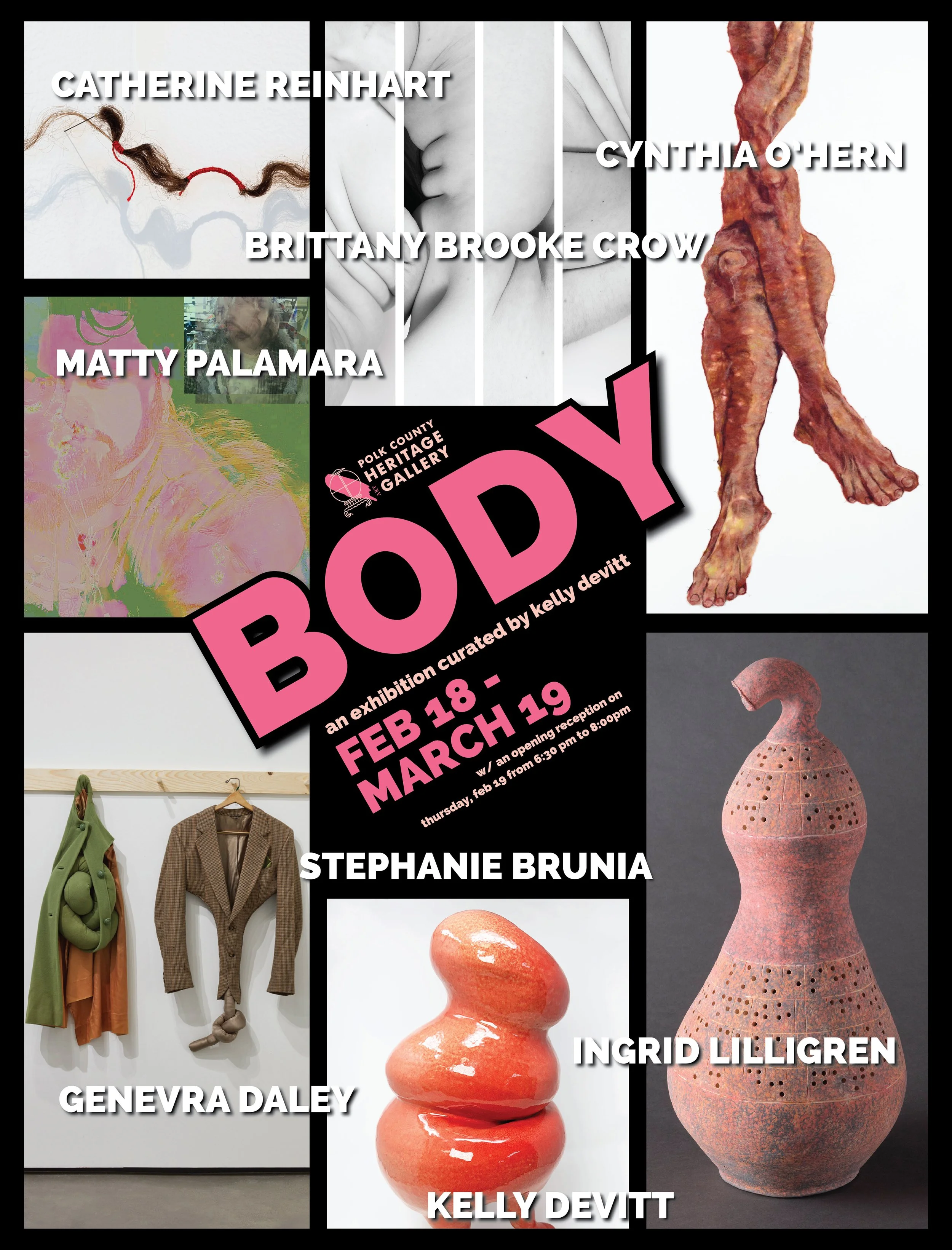

Body 2026

SCROLL DOWN

Body 2026

NOW SHOWING

February 18 - March 19

Opening reception February 19 6:30pm to 8:00pm

Through diverse media Body explores the human form as a powerful locus for identity, memory, transformation, and resistance.

Featuring 8 Iowa artists (Stephanie Brunia, Genevra Daley, Kelly Devitt, Brittany Brooke Crow, Ingrid Lilligren, Cynthia O’Hern, Matty Palamara, and Catherine Reinhart) the exhibition will present the body as both deeply intimate and inherently public.

The exhibition is curated by Kelly Devitt in conjunction with the 2025/2026 Iowa Artist fellowship, supported by the Iowa Arts Council and the Iowa Economic Development Authority.